Deceleration: The Most Energy Demanding Movement

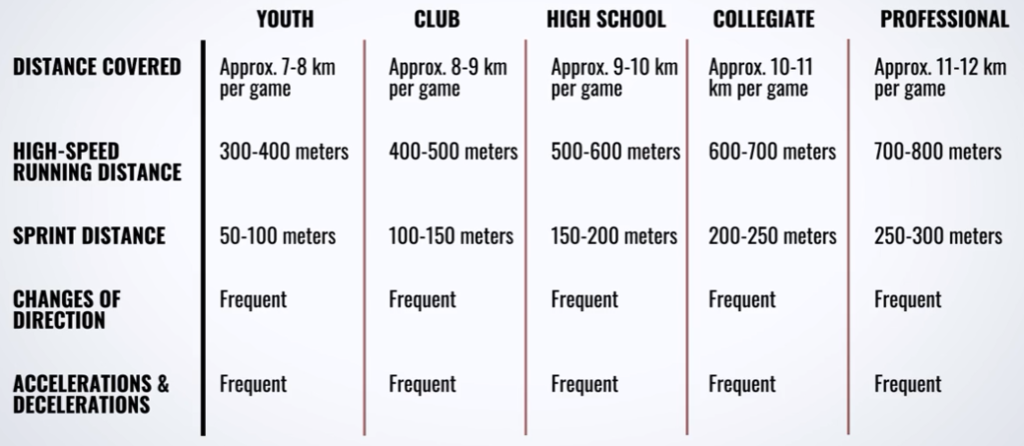

When we think of the things we do as athletes on the field, we obviously go straight to skill moves, tactics, positioning, and scoring with style! Those are all great and important, but what we are not thinking about is the direct impact our body takes during a quick deceleration and change of direction. The ability to stop forward momentum and accelerate in another direction are two of the most taxing things we can do on the body in open play. Let’s look at Jude Bellingham, the English midfielder playing at Real Madrid. If we look at the chart below, on average a world class midfielder like Bellingham will run roughly a 10k, but accel/decel frequently throughout the game. The other thing to note is that only 10% of his distance traveled in a game is spent running at top speed! That’s crazy to think about, but if you’re not directly involved in play, then you’re probably walking or lightly jogging as you wait for your moment to accelerate into space or change direction to go chase down an attacker after a loss of possession.

Soccer (Football) Midfielder Stats

It’s in this 10% of the match that most non-contact injuries happen. And these non-contact injuries don’t just happen when someone is fatigued at the end of the game. These injuries like ACL tears, hamstring pulls, or hip flexor strains occur in the first half of the game. We think that we injure ourselves when we are tired and because we are tired we get injured. It’s quite the opposite. Your body is not only fresh, but probably hyped on adrenalin and you’re working at a high rate. Because of these factors, your force output is high, your speed is high, and your focus on the game is high. Now this is one half of the issue at hand.

Why Pros Are Better at Training

On the other hand, practice is “game-like” or as close to game-like as possible, but as youth athletes, practices are small-sided games, only on one half of the field, and are usually more controlled than the game itself. These types of practices are what leads to non-contact injuries. I’m not blaming a coach or a trainer themselves. What I am blaming is the lack of tools and technology a youth team has at their disposal compared to the collegiate or professional athletes. Not saying non-contact injuries don’t occur in the professional realm as well because s*** happens, but these players are set up for greater success because of the tech they have available to them.

Two Way Youth Athletes Can Be Like the Pros

- Run at high speeds at least 1x/week – One of the main reasons athletes get non-contact injuries is because they don’t hit 100% effort on sprinting consistently enough. If they can’t hit 100% max speeds, then they can’t teach themselves to decelerate/stop/change direction as quickly as possible. Their tissues never learn to take on that stress and then we see failure of the tissues because the demand exceeds their capabilities. Research suggests that maintaining top speeds requires max sprinting every 5 days +/- 3 days (aka anywhere from 2-8 days). So a coach should be hitting sprint drills isolated and in open play at least 1x/wk.

- Have objective data to track progress in a season and let the players compete – The first point is easy enough to get the players/team moving in a positive direction. The other way to maximize athlete engagement regarding high level sprinting/change of direction/randomness is to implement technology to breed competitiveness, add randomness, and track overall progress in sessions. The Ledsreact tool is what I use for my youth athletes. It tracks all of the data you need regarding top speed, reaction time, acceleration, deceleration, and can be compared to previous test results.